5 Synthesizing Material Culture and Network Data

The previous three chapters approached the relationship between material culture and social networks from distinct but complementary angles. Chapter 3 focused on refining typological classification for projectile points, while Chapters 2 and 4 evaluated network dynamics through simulated and empirical data, respectively.

Because Chapter 4 did not incorporate the latest projectile point analysis or the most recent results from the ArchMatNet agent-based model, this chapter presents a final integrative analysis. The goal is to bring those elements together and reassess the potential for material culture networks to serve as proxies for social networks—especially in the context of the Western Pueblo region.

5.1 Multilayer Analysis

This analysis uses multilayer network analysis to evaluate how ceramics and projectile points represent different patterns of interaction. Methods follow those used in Chapter 4, with some modifications. The details of the code can be found in Appendix D.

5.1.1 Dataset and Methods

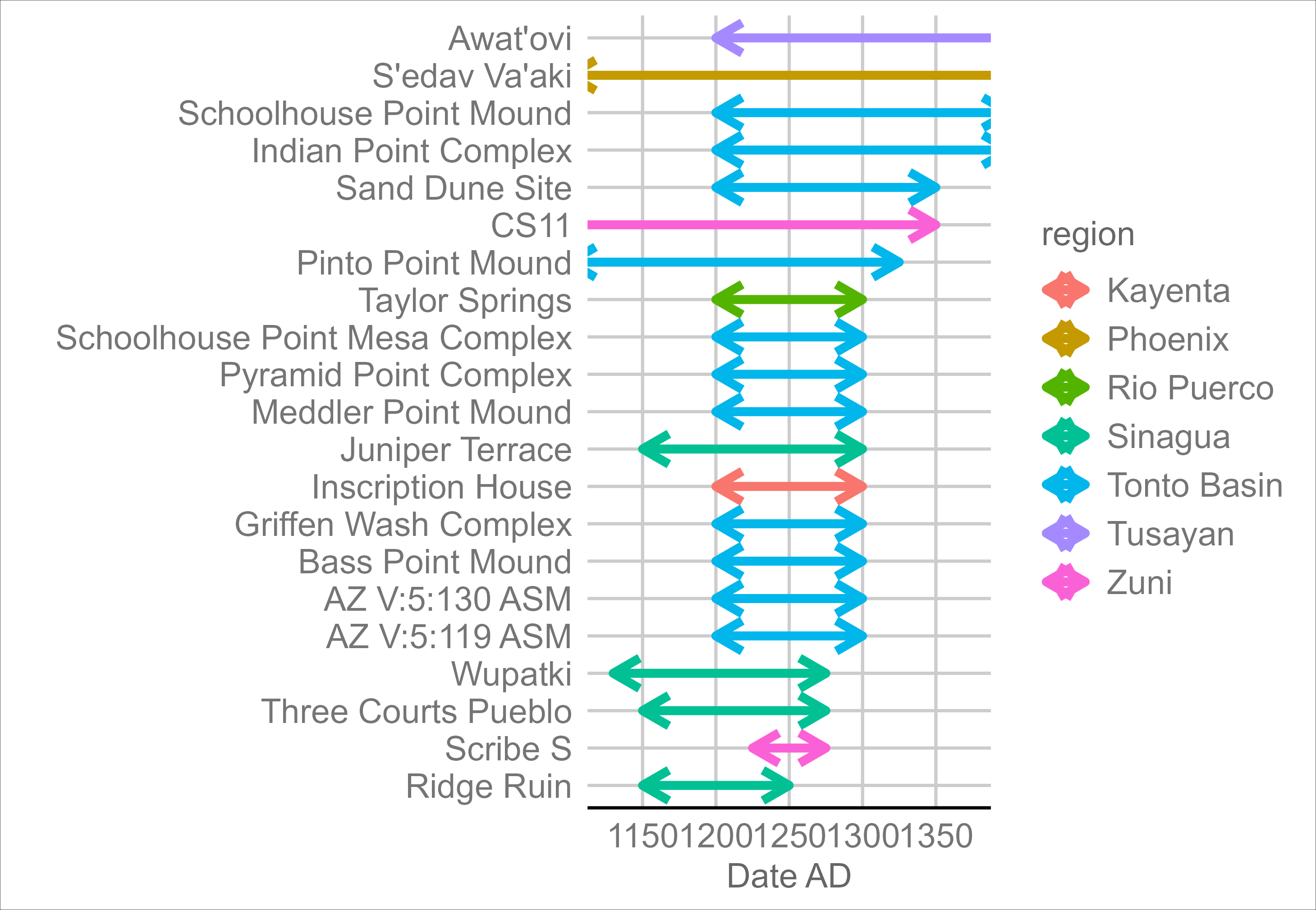

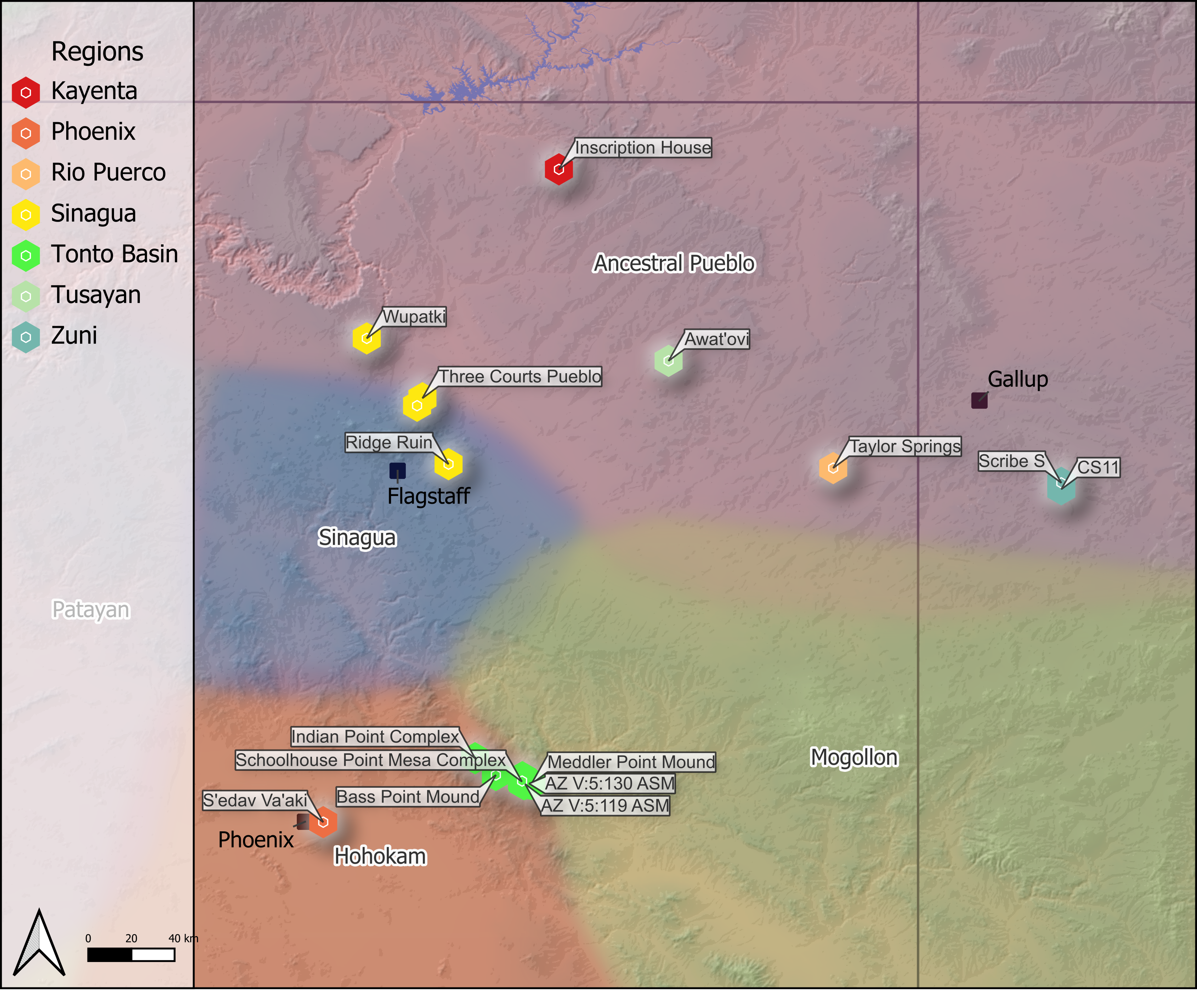

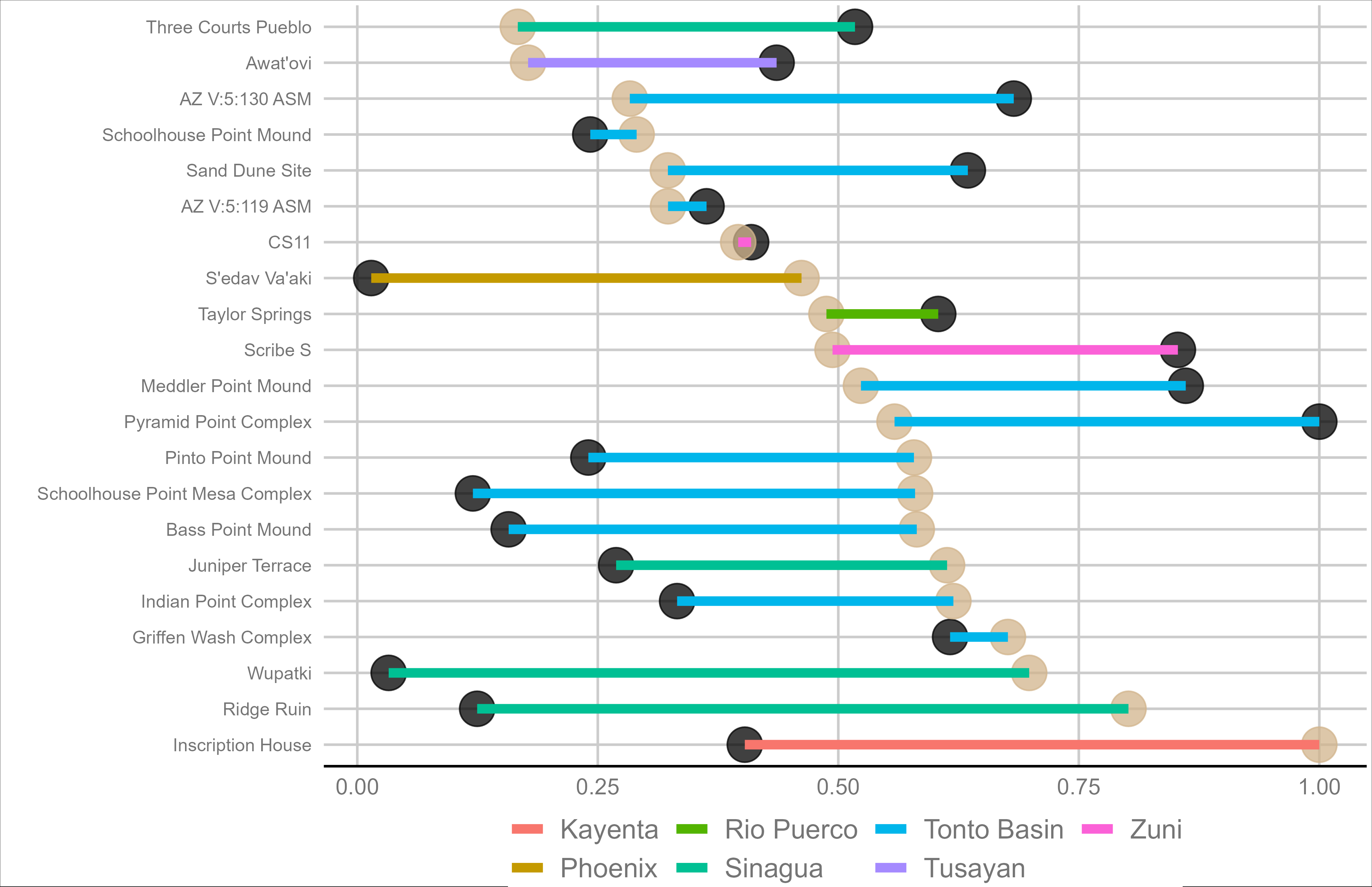

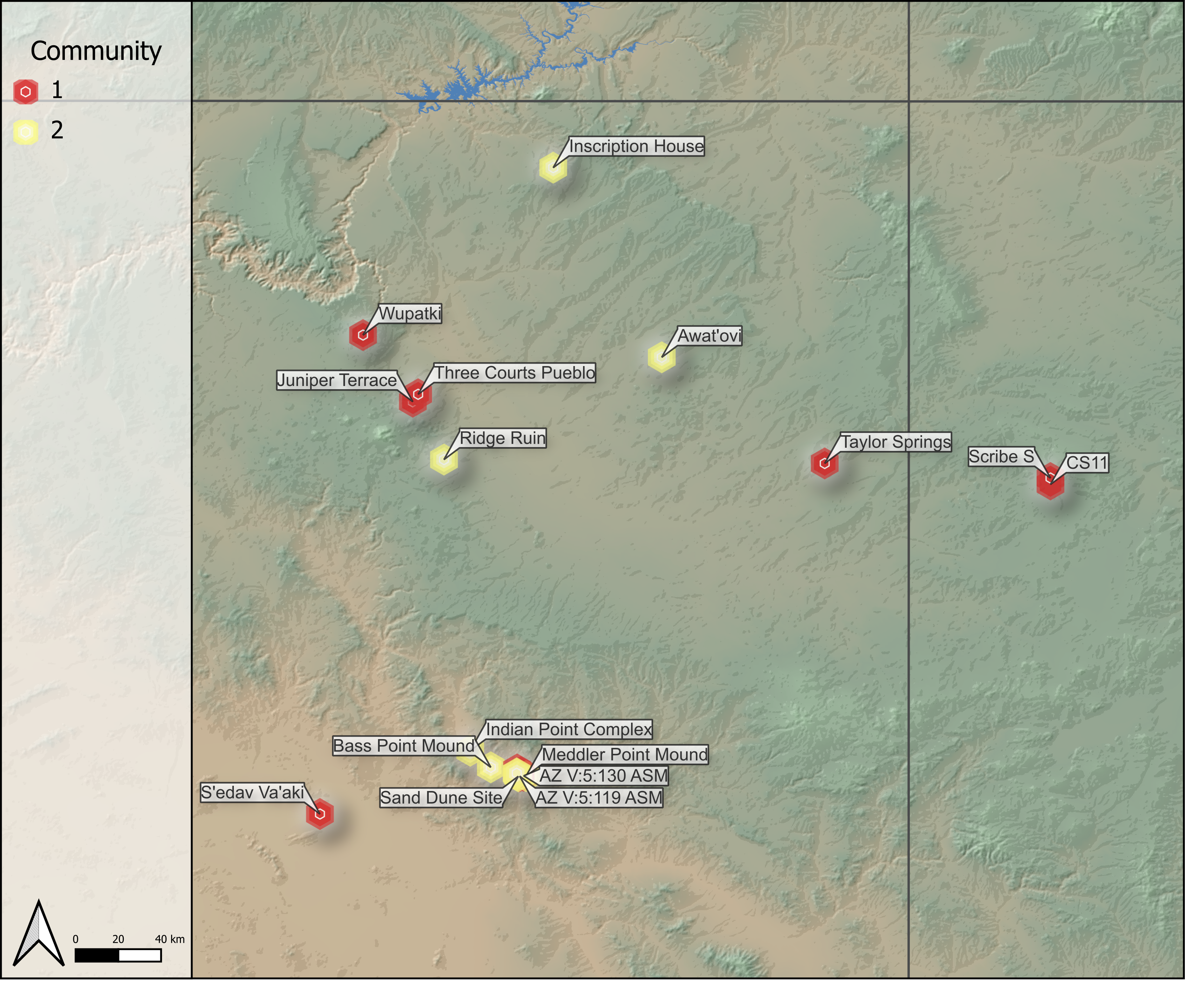

Sites were selected based on three criteria: (1) at least 25 ceramic sherds, (2) at least 5 projectile points, and (3) occupation dates between AD 1200 and 1300. Figure 5.1 and Figure 5.2 show the temporal and spatial distribution of these sites.

As in previous chapters, I created Brainerd-Robinson similarity networks based on ceramic and projectile point assemblages. Unlike earlier ceramic analyses, this version includes both decorated and undecorated types to better capture local production and use. A spatial network was also constructed based on geographic distance.

Each network was pruned by removing the weakest 50% of links and retaining only the top three ties for each site. While arbitrary, these thresholds are grounded in experimentation and insights from ArchMatNet, which indicate that strong ties are most representative of social connections. I then calculated eigenvector centrality and pairwise graph correlations for all networks.

5.1.2 Results

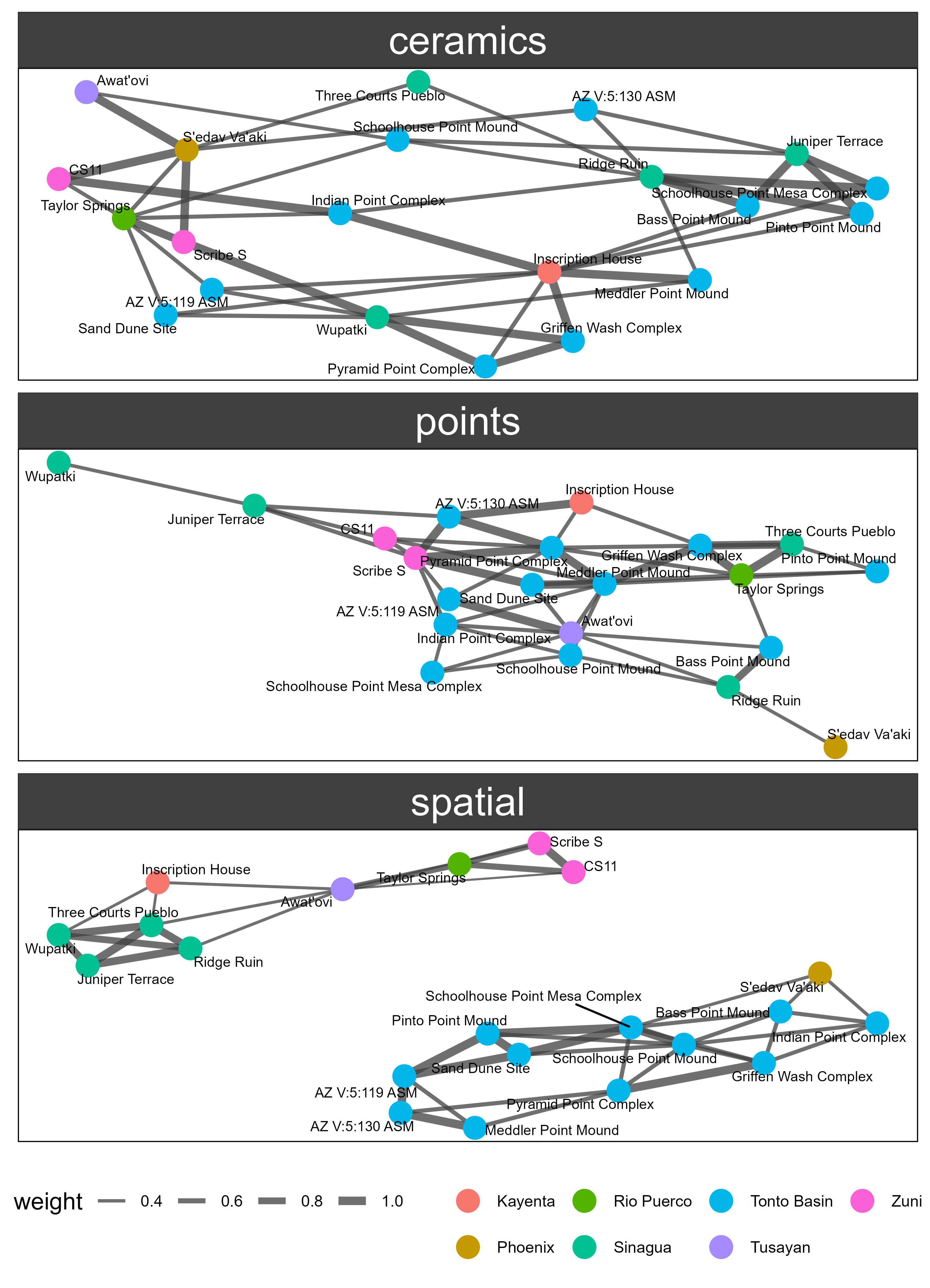

Figure 5.3 shows the three networks. The ceramic and projectile point networks form single, connected components, but they differ in structure. The spatial network shows a north–south divide, as expected based on geographic distance.

Inscription House, a Kayenta-region site, stands out in both the ceramic and projectile point networks for its strong connections to sites in the Tonto Basin, despite its geographic isolation. This pattern aligns with prior findings on Kayenta migration and shows how material culture can capture non-local interaction.

Figure 5.4 shows eigenvector centrality scores. Sites with high centrality in the ceramic network tend not to be central in the projectile point network. This again suggests that these networks reflect different social processes.

The Louvain algorithm was applied to the multilayer network (Figure 5.5), but results were inconclusive. The two detected communities did not align well with known social or regional groupings. This suggests that in this case, ceramics and projectile points should be analyzed as distinct layers rather than combined.

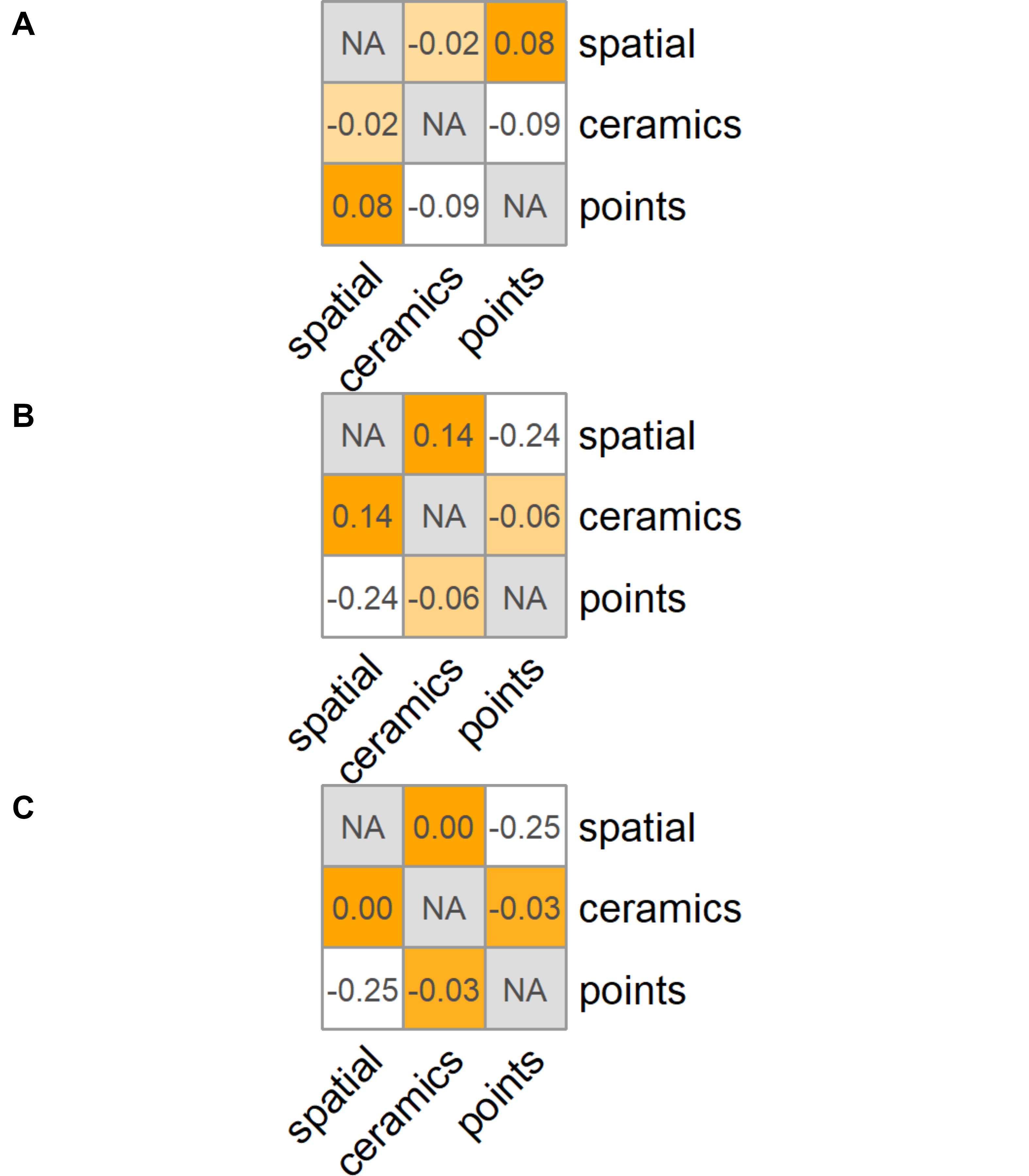

Graph correlation values further support this conclusion (Figure 5.6). Correlations between spatial, ceramic, and projectile point networks were generally low. When split into northern and southern subregions, only a weak, positive correlation was observed between ceramics and space in the north and a weak negative correlation was seen between projectile points and space in the south.

5.1.3 Multilayer Discussion

The ceramic and projectile point networks are clearly distinct. The ceramic data show regional patterning consistent with expectations and known migration patterns. In contrast, projectile point networks display less structure, though key ties–such as Inscription House and Tonto Basin–still highlight meaningful connections.

As suggested by the ArchMatNet results, distinctiveness in material culture is necessary for it to reflect social processes. Ceramic typologies are relatively localized and well-defined, making them better suited for inferring group affiliation or migration. Projectile points, while useful, may require more caution. Their forms are less visibly distinct, and the relevant parts are often hidden by hafting. The arrow shaft itself is likely more indicative of social differences, and they were often painted (Holly 2010; Justice 2002; Rudy 1953; Sinopoli 1991). This low-visibility for projectile points reduces their communicative potential in social contexts and likely ties them more closely to relational identity or individual practice.

This analysis reinforces the broader point: different types of material culture reflect different social processes. Combining them can be powerful, but only when we understand how and why they differ.

5.2 Evaluating Material Culture Networks

The core aim of this dissertation was to assess how effectively material culture networks—also referred to as archaeological similarity networks (Collar et al. 2015, p. 16)—can serve as proxies for social networks. The results from both simulated and empirical analyses suggest that material culture can meaningfully reflect social connections under certain conditions, though important limitations remain.

This evaluation was carried out through two primary avenues: (1) the ArchMatNet agent-based model (ABM), which allowed for controlled experimentation with known social and material outcomes; and (2) a case study in the central U.S. Southwest, one of the best-documented archaeological regions in the world. As has been noted, the granularity of data available in the Southwest enables studies that are simply not feasible elsewhere (Perreault 2019).

Taken together, these two approaches provide a strong foundation for evaluating material culture networks. Ethnographic studies would represent the only more direct way to answer these questions, but compiling a dataset with detailed records of both material culture and social relationships remains a major challenge.

As discussed in Chapter 2, Golitko’s study (2023) provides a rare example of such an ethnographic approach. His work revealed weak correlations between social interaction and material culture networks, and centrality measures performed poorly. These results mirror many of the findings presented here and reinforce the need for caution when interpreting archaeological networks.

The results from this dissertation confirm that Golitko’s findings should be expected in certain contexts. That said, the discrepancies in strength between his results and those from ArchMatNet may be due to limitations in the bone dagger dataset, the nature of the interaction data, or the binary representation of ties. Still, his study offers an important benchmark and underscores the utility of using ABMs like ArchMatNet to test the assumptions behind archaeological network inference.

5.2.1 ArchMatNet

The ArchMatNet model provided a robust experimental tool for assessing how well material culture networks can reflect social interaction under controlled conditions. One of the most important takeaways is that material culture networks can perform well when traits are sufficiently variable and transmission is structured by both prestige and conformity. But when those conditions are not met, material culture networks can become unreliable or misleading.

One consistent finding was that material culture networks tend to overemphasize weak ties while slightly dampening strong ones. This smoothing effect should be kept in mind when interpreting archaeological similarity networks.

ArchMatNet also showed that different classes of material culture can generate different network structures—an observation echoed by only a few archaeological studies (Giomi 2022; c.f., Mills et al. 2015; Upton 2019). These differences are important. If we interpret network structure without accounting for material-specific dynamics, we risk mischaracterizing the social phenomena we hope to understand.

Trait visibility also proved important to the model. Highly visible traits were designed to be more likely to be copied and dispersed, while low-visibility traits were less likely to be copied. This aligns with the theoretical model discussed in Chapter 1, in which high-visibility traits relate to categorical identity—used to signal group affiliation—while low-visibility traits reflect relational identity, grounded in close, often face-to-face interaction. The visibility parameter in ArchMatNet confirmed that this parameter has a strong outcome on the model results, although the precise effects require further study.

5.2.2 Central U.S. Southwest

Chapters 3, 4, and the synthesis presented here draw on datasets from the central U.S. Southwest to evaluate how well material culture networks align with known patterns of social interaction. These results generally support the findings from ArchMatNet: while material culture can signal interaction, results vary depending on the material type and social context.

The network analysis in Chapter 3 was limited in scope, but the more extensive analyses in Chapters 4 and 5 show that material culture networks can capture known processes, such as the Kayenta migrations into the Tonto Basin. Importantly, these analyses also reinforce the ArchMatNet finding that different artifact classes–ceramics and projectile points, in this case–generate different network structures.

This difference may reflect distinct social processes. Ceramics tend to be more localized and stylistically constrained, allowing clearer inferences about group identity and affiliation. Projectile points, on the other hand, are often distributed across broader regions and may not vary enough to track local social dynamics, especially when starting traits are homogeneous. In such cases, as shown in ArchMatNet, the resulting networks are weak proxies for social interaction.

Even so, broad patterns—such as regional connectivity during periods of migration and aggregation, such as the periods studied here, are well represented in the material culture networks. These patterns reinforce long-standing interpretations of regional social organization while offering new ways to quantify and model them. Moreover, the new projectile point typology developed in this study highlights the value of analyzing multiple types of material culture to capture different dimensions of interaction.

5.3 Computational Archaeology

This dissertation draws on a number of computational methods—including agent-based modeling, network analysis, geometric morphometrics, GIS, and machine learning—to address a central question in archaeology: how do patterns in material culture reflect underlying patterns of social interaction?

These methods were not chosen for novelty’s sake, but because each provided the most appropriate framework for a specific part of the research. When used in concert, these approaches allowed for a more comprehensive and theoretically grounded understanding of the material and social processes at play. Each comes with its own strengths and weaknesses, and this dissertation demonstrates that combining multiple methods can help balance those trade-offs.

The agent-based model was arguably the most powerful tool in this project. It allowed for systematic testing of specific variables—learning mechanisms, visibility, population structure—while holding other factors constant. This level of control is impossible in real-world archaeological settings. However, like any model, it is limited by its assumptions. It cannot replicate past societies, but it can reveal the conditions under which archaeological proxies are more or less reliable.

Geometric morphometric (GMM) analysis proved valuable but also revealed its limits—particularly for classifying projectile points. Chapter 3 showed that GMM is most effective for understanding variation within a type rather than distinguishing between types. Projectile points exist on a continuous morphometric spectrum, and without considering categorical attributes, GMM alone is insufficient for typology construction. That said, it was useful for identifying consistent shape clusters and for quantifying variation in a replicable way for constructing the typology used here.

Machine learning, by contrast, showed greater promise for classification once a reliable training dataset was created. Its strength lies in scalability and consistency, and when paired with a well-constructed typology, it can be a powerful tool for archaeological classification. Unlike GMM, machine learning can incorporate both geometric and categorical variables, offering a hybrid approach that builds on the strengths of each.

Together, these computational approaches provided a diverse toolkit for addressing a longstanding archaeological problem. More importantly, they offered new ways to evaluate assumptions, test models, and refine interpretations.

5.4 Conclusion

This dissertation set out to examine the relationship between material culture and social networks. While this is a common assumption in archaeological network studies, it has rarely been tested in a systematic way (c.f., Golitko 2023). The goal here was to move beyond assumption and evaluate the conditions under which material culture can serve as a reasonable proxy for social ties.

I used a combination of agent-based modeling, geometric morphometrics, machine learning, and multilayer network analysis to address this question and build my dataset. The ArchMatNet model, introduced in Chapter 2, allowed for controlled testing of these relationships. The model showed that material culture networks can approximate interaction networks, but only under specific conditions—particularly when traits vary significantly between groups. Importantly, material culture tends to have a smoothing effect: strong ties are weaker, but weak interactions are over-emphasized in the material culture networks. This should serve as a caution for archaeological interpretations based solely on artifact similarity.

In Chapter 3, I developed a regional projectile point dataset and showed that geometric morphometrics, combined with machine learning, can replicate and improve on traditional typologies. The new typology–developed for this research project, not for general usage–was based on measurable attributes and reduces subjectivity. It also allows for scalable classification across large datasets. Additionally, the methods are not restricted to the Southwest but are adaptable to other areas.

Chapter 4 integrated ceramics, architecture, and projectile points into a multilayer network analysis focused on Tonto Basin. The different material categories produced distinct network structures, which likely reflect different aspects of social life. Ceramic and architectural patterns—being more visible and often tied to group-level identities—appear to represent categorical connections. In contrast, projectile points showed more variation at the individual or household level and likely reflect relational identities tied to learning and craft practice. These differences may also correspond to gendered social roles, with ceramics more associated with women and projectile points with men.

Taken together, the results across these chapters show that material culture networks can be useful proxies for social networks, but only if we’re careful about the assumptions we bring to the analysis. Visibility, trait variation, and modes of learning all affect how well material patterns track with interaction. The findings here point to the value of using multiple proxies, evaluating each on its own terms, and avoiding overconfidence in neat, symmetrical network structures.

Ultimately, this dissertation contributes a framework for evaluating how material culture relates to social processes and how different lines of evidence can be used to model interaction at multiple scales. The methods presented here are transferable to other datasets and regions, but future work will need to account for regional variation and continue refining the link between material and social networks. Material culture is not a perfect mirror of past social life, but under the right conditions, it can reflect it in meaningful and interpretable ways.