4 Investigating Material Culture through Multilayer Network Analysis in Tonto Basin

4.1 Introduction

Network science has many applications for archaeologists, and it can be particularly useful for breaking out of traditional spatial categories and examining data through new lenses (Feinman and Neitzel 2020; Holland-Lulewicz 2021). Multilayer network analysis combines multiple networks into one analytical framework (Kivelä et al. 2014). Social systems are complex webs of interrelations. There is too much involved to model the material culture of even a technologically simple society, but certainly analyzing more than one type of material culture provides an improved understanding of the social dynamics involved in the networks of interaction we wish to understand. Yet, there are few examples of multilayer networks in archaeology (e.g., Giomi 2022; Upton 2019) and none I am aware of that extend beyond ceramics.

Network studies are particularly prominent in the Southwest, and there are examples of network studies that consider multiple types of material culture. To name just two: Mills and colleagues (2013) used ceramics and obsidian to understand the transformation of large-scale social networks; Peeples (2018) used ceramics and architecture to understand identity and social change in the Cibola region. This paper is an application of multilayer network analysis that seeks to further network research by examining multiple types of material culture in one framework. Given the frequent focus on single types of artifacts in network research, a primary question I seek to address is whether networks based on different types of material culture are positively correlated. This matters because archaeologists often make inferences based solely on ceramics or other types of material culture. Evidence regarding the ways material culture co-vary will help give better context to these studies. Furthermore, I seek causal explanations for the co-variance, or lack thereof, for material culture in the case study I present here.

Tonto Basin holds great potential for archaeological research due to the large cultural resource management projects conducted in the region primarily in the 1980s-1990s (Ahlstrom et al. 1991; Ciolek-Torrello et al. 1994; Doelle et al. 1992; Rice 1998), as well as the large number of syntheses and other studies focusing on the area (e.g., Jeffrey J. Clark and Vint 2004; Dean 2000; Elson et al. 1995, 2000; Lange and Germick 1992; Lyons 2003; Lyons and Lindsay 2006; Oliver 2001; Stark et al. 1998; Watts 2013). This analysis uses data from the Roosevelt Platform Mounds Study (RPMS), the largest of these projects (Rice 1998), to examine basic architectural data, typed ceramics, and data from a recent projectile point analysis (Bischoff 2023). There are two null hypotheses tested in this analysis: (1) that the data is spatially correlated–meaning that sites nearest to each other will be most alike–and (2) that the architecture, ceramics, and projectile points will all be positively correlated–meaning that similar types of architecture, ceramics, and projectile points will be found at the same sites. In reality, I expected significant variation between these types of material culture. As will be demonstrated, the results demonstrate substantial differences between the various networks. I posit that differences in the ceramic and projectile point networks (hereafter point networks) can be contributed to gender dynamics in the production and distribution of these artifacts.

4.2 Tonto Basin

Tonto Basin is in east-central Arizona and features Tonto Creek flowing from the Mogollon Rim into the Salt River (Figure 4.1). Parts of the region have been intensively studied, while certain time periods and much of the uplands have been less intensively sampled (see Jeffery J. Clark and Caseldine 2021 for a recent overview). The basin was conveniently located along regional travel routes, allowing major settlements–particularly those with platform mounds–to participate and benefit from this exchange (Caseldine 2022; Wood 2000, pp. 129–133). The junction of the Salt River and Tonto Creek now forms Roosevelt Lake since the damming of the confluence of the Salt River and Tonto Creek. It was the expansion of the dam that precipitated the RPMS and its related projects in the late 1980s-1990s. Some important regional differences may have differentiated sites along the Salt River and Tonto Creek arms of Roosevelt Lake (Lyons 2013; Simon and Gosser 2001) based on non-local ceramics and obsidian. All of the artifacts/data from the RPMS project are hosted at the Center for Archaeology and Society at Arizona State University, and the data in this study come exclusively from this project.

Tonto Basin was occupied, although likely not continuously, from the Archaic through the late Classic period. The height of occupation, particularly the sites excavated during the project, dates between AD 1275 and 1325, which corresponds to the Roosevelt Phase. The Roosevelt phase is notable for the appearance of Salado pottery and platform mounds–probably introduced from the Phoenix Basin (Elson 1996). Moderate occupation continued into the Gila phase (AD 1325-1450), which was characterized by population loss and aggregation into larger sites. This phase marks the end of recognizable occupation in the area until the historic period.

Tonto Basin’s position in a border zone between the Hohokam, Mogollon, and Ancestral Pueblo regions has received much attention (e.g., Caseldine 2022; Jeffery J. Clark 2001; Elson and Lindeman 1994; Lyons 2013; Wood 2000). Of particular note is the presence of masonry roomblock architecture and pottery uncharacteristic of the local Hohokam traditions, which has been interpreted as Kayenta immigration into Tonto Basin (Jeffery J. Clark 2001; Lyons 2003; Lyons and Lindsay 2006; Stark et al. 1998), although some have attributed the architectural changes to warfare or population aggregation (Oliver 2001; Wood 2000). This migration into the Tonto Basin was part of a larger migration from north to south and is associated with the origin of the Salado phenomenon. Salado pottery production (formally known as Roosevelt Red Ware) was widespread across southern Arizona and southwest New Mexico, but often the largest sources of production was centered at the location of a former Kayenta enclave (Neuzil 2008). The connection between immigration and Salado pottery suggests that sites with roomblocks may have higher centrality in ceramic networks. Having high centrality means they have more connections to other nodes (i.e., sites). The presence of migrant communities in Tonto Basin invites questions regarding the relationship between sites–particularly between migrant and local communities. A network approach is an ideal way to examine the relationships between settlements. Evidence that projectile points move between communities in the Tonto Basin (e.g., Sliva 2002; Watts 2013) indicates that this is also a productive line of analysis, and one that is less-commonly pursued compared to architecture and ceramics.

4.3 Data Collection

The ceramic data was collected from the cyberSW database (B. Mills et al. 2020). The architectural data and chronological assignments were obtained from the original RPMS reports (see Rice 1998). An Access database available on tDAR (Roosevelt Platform Mound Study (RPMS) 2014) was used for correlating proveniences between projectile points and ceramics. The projectile point data were obtained from collections held at the Center for Archaeology and Society at Arizona State University.

The major limiting factors in this analysis were the presence of complete projectile points and the dating of artifacts. The sample was limited to all sites in the RPMS database with three or more complete projectile points. The majority of the occupation for the sites in this study occurred during the Roosevelt phase. Some sites lasted into the Gila Phase and some were occupied earlier. To account for chronological problems, the ceramic assemblages were apportioned following Roberts and colleagues (Roberts et al. 2012) using a uniform probability density analysis procedure described by Ortman (2016) and implemented in R [RCore2022-a] by Peeples (2021). The R script used to calculate this is included in Appendix C. Essentially, this Bayesian procedure uses the dating of chronologically sensitive ceramic types to estimate the probability that a sherd was deposited at a particular time. The entire assemblage can then be divided into intervals based on these probabilities. Ceramic dating can be troublesome in Hohokam archaeology, but fortunately there are sufficient chronologically sensitive wares, in particular trade wares, to successfully apply this method here. I divided the assemblages into 25 year intervals and then assigned each sherd to either the Roosevelt, Gila, or “other” phases. Only the Roosevelt phase had sufficient data to proceed. Ceramic data from the other phases were dropped. I then used cross-dating to find projectile points located in contexts with sherds that were clearly from the Gila phase and removed these from the analysis. This further reduced the projectile point sample and the number of available sites. Table 4.1 lists the 10 sites with sufficient data to include in this study with the types of architecture present and total number of ceramics and complete projectile points found at each site.

4.4 Network Analysis

Network analysis is a flexible tool for analyzing many types of data (see Brughmans and Peeples 2023). The key element is that some way must be determined to tie each entity together. This analysis uses sites as nodes in the network and some type of similarity as a tie to connect each node. Each type of similarity depends on the type of data. The networks in this study are not meant to represent complete reconstructions of past networks. Only a limited number of sites are included. They are not meant to be reconstructions of face-to-face interactions. These networks are a way to represent data. They describe how closely connected nodes are to each other.

4.4.1 Defining Networks

Network approaches are best suited where the relationships between entities are of primary interest. In this case, the entities are defined as archaeological sites. The archaeology sites in turn represent a group of individuals who lived or visited the area of the site and left material remains behind. Ideally, studying social relations would be approached at the individual level, but rarely can archaeologists address archaeological data with that level of specificity. Watts (2013), however, used projectile points from Tonto Basin in just such a study. His analysis of flake scar patterning identified individual knappers, or at least clusters of people with similar knapping styles, and the distribution of their projectile points around Tonto Basin. He found strong connections between many parts of the eastern Tonto Basin. Unfortunately, this study will only attempt a site-level analysis. Watt’s study does, however, illustrate how relations can be defined between nodes in a network analysis. He used similarity networks where the points that had similar flaking styles were connected. Similarity networks are a commonly used type of network in archaeology (e.g., Birch and Hart 2018; Borck et al. 2015; Cochrane and Lipo 2010; Golitko and Feinman 2015; Lulewicz 2019; B. J. Mills, Roberts, et al. 2013; Peeples 2018; John Edward Terrell 2010). These studies use a variety of artifacts and methods to construct their networks, but each has demonstrated the utility of network methods within archaeological contexts. This study also uses similarity networks to group sites by similarity in ceramic assemblages and similarity in projectile point forms.

4.4.2 Interpreting Networks

It can be difficult to understand how a similarity network is related to a past social network. What kinds of interactions are represented by similarities in projectile points or in ceramics? Answering this question is also a crucial step in interpreting networks. One way to examine relations between individuals who make or use similar types of projectile points or pots is to talk about identity. Identity can be a troubling topic for anthropologists. There are numerous meanings given to it and numerous scales at which it applies (Brubaker and Cooper 2000), but Peeples (2018) has introduced an approach that unites prior discussions into a simple model. This approach views identity as existing along two axes: one categorical and the other relational. Relational identification is the process of identifying with someone due to frequent interaction. Categorical identification is the process of identifying with someone because you belong to a recognized social group. For example, members of the same moiety would share a categorical identity. They would likely also share a relational identity if they frequently interacted. These identities can be reflected in material culture. Pottery makes a good example. Peeples (2018, p. 151) notes that bowls in the Cibola region were sometimes painted with a bright, red slip with designs painted on the interior and they were among the first in the Southwest to have designs on the exterior. This is a strong indication of categorical identity. The potters were attempting to make a clear signal for whoever saw the pot. Relational identity can be seen in the way the potter prepares the clay recipe and smooths the coils. The particulars of these actions would be learned from close interaction with a teacher or other potters. In this way, relational identity can be compared to communities of practice (Lave and Wenger 1991; Wenger 1998).

In this analysis, I argue that ceramics and architecture are more likely to represent categorical identity. The architecture discussed is highly visible and representative of group membership. The ceramics are grouped into types based primarily on decoration, which is strongly indicative of group membership. What this means is that links between nodes in the ceramic network are more likely to indicate belonging to a similar social group. The details of architecture and ceramics used in this study are discussed in a future section, but it is important to note that these designations as categorical or relational are contextually dependent on this study. Clark (2001) has an excellent discussion on material culture and its relationship to identity. He identifies certain patterns, but his synthesis and other research (Carr 1995a, 1995b; Dietler and Herbich 1998; Gosselain 1998, 2000, 2016; Hodder 1982; Huntley 2008; Lemonnier 1986; Lyons 2003; Sassman and Rudolphi 2001; Stark et al. 1998; Wiessner 1983, 1997) strongly indicates that the relationship between material culture and identity is culturally relative. Projectile points can in some cases indicate group membership (Wiessner 1983, 1997), but in this case the triangular and side-notched points were likely used for different purposes (see Chris Loendorf et al. 2015; Sliva 2002). Styles were difficult to determine for the original researchers (Rice 1994), and I had the same difficulty. In my opinion, the subtle differences between projectile point outlines are more representative of interactions between knappers than markers of group identity for this particular case. This is indicative of relational identity. There are no environmental reasons to assume differences in projectile points, as each site was in a similar ecozone. Each hunter would have been using the points for the same game and differences in point styles would have been primarily cultural (Sliva 2002).

There is one other aspect to these relations that I believe played an important role. A central way people identify themselves is by gender. Gender roles also vary in complex ways, but for the purposes of this analysis I will use a simplified model. Women made pottery and men made projectile points. This was not always true of course, but this fits the available data and expectations for the Hohokam (Crown and Fish 1996; Harry and Huntington 2010; Shackley 2005; VanPool and Savage 2010, p. 253; Whittlesey 2010). An examination of the ethnographic record for the O’odham people, recognized descendants of the Hohokam, provides additional references that women made pottery (Bahr 2011, p. 4; Castetter and Underhill 1935, pp. 5–6; Chona 1936, p. 44; Joseph et al. 1949, p. 57). An examination of the burial record for the RPMS study shows no obvious indication that women made pottery, only that both men and women were buried with pottery (Christopher Loendorf 1998, Table 10.7). On the other hand, projectile points were almost exclusively buried with males. This does not mean that a man could not move pots from one site to another or that a woman could not do the same with a projectile point, but, in general, differences in point and ceramic networks are most likely to indicate differences in gender networks.

Shackley (2005), using projectile point typology data from Hoffman (1997) as well as obsidian provenience and ceramic data for preclassic Hohokam sites in the Phoenix Basin, found evidence for three distinct projectile point traditions. Shackley and Hoffman believe these may correlate with warrior sodalities, and Shackley argues that the male projectile point exchange systems functioned in different ways than the female ceramic exchange systems. In this case, the projectile points likely correlate with a categorical identity, but this provides an example of how men and women’s networks have been argued to vary in Hohokam archaeology.

From this discussion, I expect the ceramic and point networks to differ in two ways. I expect the ceramic network to represent categorical identity among women, and I expect the point network to represent relational identity among men. This makes the networks somewhat more difficult to compare. Ideally, we would have networks of the same identity type, but it does provide the expectation that we should see significant differences in the networks.

4.4.3 Network Similarity

The network for architecture, ceramics, and projectile points, were created using the Jaccard similarity coefficient (Jaccard 1912) to determine the links between each site. This is calculated as follows:

\[ J(A,B) = |A \cap B| / |A \cup B| \]

\(A\) and \(B\) are sets, \(|A|\) represents the number of elements of set \(A\), \(\cap\) represents the set of elements that are common to both \(A\) and \(B\), and \(\cup\) represents the set of elements that are in either \(A\) or \(B\) or both. The Jaccard similarity \(J(A,B)\) is the ratio of the size of the intersection of sets \(A\) and \(B\) to the size of the union of sets \(A\) and \(B\). This is a simple measure of similarity that does not take into account abundance. It was chosen due to the large differences in sample sizes between sites for the ceramics and projectile points and because count data were irrelevant or not readily available for the architectural data.

| id | Site | Area | Architecture | Ceramics | Projectile Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AZ U:4:032 (ASM) | Cline Mesa | compound | 133 | 3 |

| 2 | AZ V:5:119 (ASM) | Livingston | compound | 25 | 3 |

| 3 | Bass Point Mound | Rock Island | platform mound | 479 | 13 |

| 4 | Cline Terrace Mound | Cline Mesa | platform mound | 17333 | 45 |

| 5 | Indian Point Complex | Cline Mesa | compound, roomblock | 1024 | 3 |

| 6 | Pinto Point Mound | Livingston | compound, platform mound | 1109 | 21 |

| 7 | Saguaro Muerto | Livingston | roomblock | 373 | 5 |

| 8 | Sand Dune Site | Livingston | compound | 589 | 12 |

| 9 | Schoolhouse Point Mesa Complex | Schoolhouse Mesa | compound | 2671 | 12 |

| 10 | Schoolhouse Point Mound | Schoolhouse Mesa | platform mound | 12782 | 9 |

The types of similarity used in this study are varied depending on the type of network. Part of this analysis is a visual approach and some of the methods require non-weighted links, thus I use only the strongest links. There is rarely a clear dividing line between similar and not similar. This can be a challenge for network analysis, because networks can have every node connected to each other. The decision to binarize a network–remove the weakest links and then consider each link of equal value–has its drawbacks (Peeples and Roberts 2013) but is necessary in this case. A solution is to assign weights to each link that defines the strength of the tie. These networks are often difficult to visualize, and some network algorithms do not allow for weights. A common approach is to keep only the strongest ties by either ranking the ties or using a cutoff value.

I used ranked links to keep consistent values between networks. This involved calculating the strength of similarity between each site in the network and then ranking the strength of similarity. The top n connections (n varies between 3 and 10) between each site were kept and the rest were discarded. In practice, not every node will have the same number of connections. Some may have fewer ties if there are not enough nodes that are similar. More ties can exist when there are ties in the ranks. Because the network is not directed (meaning the ties indicate similarity in both directions) one node can have several ties pointing to it because that node was in the top n of multiple other nodes. In the latter case, this is a good indication of a central node in the network. Because I am using several types of networks, there is no common cutoff value I can use for the number of ties to keep. Instead of arbitrarily picking one value, I have calculated each metric using networks composed of the top 3-10 ties. Meaning that each metric is calculated for a network composed of ties with the top 3 connections, and the process is repeated for new networks composed of ties with the top 4 connections, and so forth. Examining the range of these metrics provides a more robust analysis.

4.4.4 Network Analysis Methods

Two network metrics are discussed in this analysis: eigenvector centrality and multilayer network correlation. Node centrality is a common way to quantify networks (Borgatti 2005). Centrality is a measure of the influence of the node on the network. Nodes with higher centrality generally derive or generate greater benefits from the network. For example, if I have many friends, then I can call in more favors. Eigenvector centrality is one way to measure node centrality and is commonly used in archaeology. This metric describes how well a node is connected to the network as a whole and is helpful in comparing different networks containing the same nodes. For example, if my friends have many friends, then I will have a greater advantage then someone with an equal number of friends, but whose friends have few friends. Essentially, this is a way of measuring second-order and beyond connections. Eigenvector centrality is also more robust to missing nodes than other measures (Peeples 2017), a major problem in most archaeological studies.

A single network is typically used in network analyses, but multilayer networks can be more informative. Multilayer networks are layered networks where nodes have different types of connections (Kivelä et al. 2014). In this analysis, each network has the same nodes–each archaeological site–but different types of relationships between them. The combination of these individual networks is a multilayer network (also called a multiplex network). Multilayer networks allow for methods to be applied on multiple networks at once (see Bródka et al. 2018). The method applicable to this analysis is layer correlation. Either Pearson or Spearman rank correlation can be computed to determine the strength and direction of correlation between each layer. Bródka and colleagues (2018) have provided an R (Team, R Core 2024) package to compute these statistics. They recommend the Pearson correlation in most circumstances. I use the results of the Pearson correlation, but the Spearman correlation provided similar results. Eigenvector centrality was mentioned in the previous section, but it is also calculated as a multilayer eigenvector centrality. In this case the centrality measure is simply the mean of the eigenvector centrality for each separate layer, as the layers are not interdependent (Frost 2022). Multilayer eigenvector centrality results are only presented for the combination of ceramic and point layers. These networks can be thought of as dependent variables for the spatial and architectural networks–meaning spatial distance and architecture are considered important variables determining the structure of the ceramic and point networks.

The robustness of results was tested by randomly sampling the underlying network matrices 1,000 times and comparing the results to the random samples to obtain a p-value. This provides a baseline that determines how likely it is to obtain a given result by chance.

Certain caveats must be acknowledged. All archaeologists deal with missing data, which can greatly affect the results of analysis. Network analysts have grappled with this question and often use resampling or similar methods to deal with this problem (Bischoff et al. 2021; Bolland 1988; Borgatti et al. 2006; Brughmans and Peeples 2023; Costenbader and Valente 2003; Galaskiewicz 1991; Gjesfjeld 2015; Lee et al. 2009; Rivera-Hutinel et al. 2012). Regardless of statistical methods, unaccounted for biases will still produce invalid network results (Bischoff et al. 2021). The most important bias that may affect these findings is chronology. For example, Bass Point Mound and Cline Terrace Mound were probably not occupied at the same time (Jacobs 1997; Lindauer 1995). Does that invalidate the network analysis? I do not think so. While the networks involve nodes as sites, what the networks are really meant to represent are groups of people. Furthermore, they are not individuals, but the aggregate decisions of people over more than one generation. Current models of Hohokam social groups suggest a certain residential stability (Craig and Woodson 2017, p. 336). Perhaps the residents of these sites were not physically located at the site at the same time as the other inhabitants were located at their site, but they may have been at another nearby location. The spacing of settlements may indicate a corporate form of social organization (Jeffrey J. Clark and Vint 2004; Rice and Oliver 1998, p. 96). If this is accurate, then the communities inhabiting the sites may likely have existed in some form prior to the establishment of any particular site and have continued on. It is these communities that the network analysis is attempting to capture. Still, evidence indicates that most sites were contemporaneous. For example, Cline Terrace Mound and Schoolhouse Point were most probably occupied at the same time (Lyons 2013). It is best, though, to think of these interpretations as estimations based on incomplete data and to recognize that these networks are an analytical tool and not a representation of an ancient face-to-face interaction network.

4.4.5 Spatial

The simplest network is the spatial network. This network was created by calculating the Euclidean distance from every site to every other site. Euclidean distance is a shortcut that does not represent actual travel routes. Least cost paths provide more accurate data (see Caseldine 2022 for an application in Tonto Basin), yet an analysis in similar terrain indicates that for distances longer than those in this study the benefits of least cost path distances in place of Euclidean distance are negligible (Bischoff 2017). Least cost paths are also hampered by the presence of Roosevelt Lake and other modern impacts on the landscape. The spatial network created here is equivalent to proximal point analysis, which was used in one of the earliest network studies in archaeology (John E. Terrell 1977) and continues to be used to study potential pathways of interaction (see Broodbank 2000; Collar 2013). The inclusion of a spatial network serves as a null hypothesis to test the other networks against.

4.4.6 Architecture

The architectural components consisted of compounds, roomblocks, and platform mounds. Compounds were the typical residential structures in the area and featured multiple houses built from masonry and/or adobe around a courtyard. Platform mounds were formed from large masonry and adobe retaining walls with a cell-like interior filled with trash and rubble. They were common in the Hohokam region throughout the Classic period. Some sites had pit houses dating to earlier occupations, so these few pit houses were removed from the analysis (see Rice 1998). Each site was classified as a platform mound if one was present regardless of other architecture or as a roomblock if a platform mound was not present regardless of other architecture. Thus, if a site is labeled a platform mound it may have other architecture. Sites were labeled in this manner to emphasize the most distinctive form of architecture, but all types of architecture were present in the analysis, and all architectural features included in the analysis can be seen in Table 4.1.

4.4.7 Ceramics

The ceramic network consists of 28 decorated types (plain wares and most undifferentiated types were removed from the analysis. The ceramic data was accessed from the cyberSW database (B. Mills et al. 2020), which keeps the full citations for the ceramic data. The ceramic data was merged with the projectile point and architectural data by site names using the semi-automated ArchaMap application (part of the CatMapper family of tools, Hruschka et al. 2022), which stores the merge for reproducibility (https://catmapper.org/archamap/AD944). The standard caveats for ceramic analysis apply to this analysis as well–problems with sherd misidentification and other data errors.

4.4.8 Projectile Points

The ceramic and architectural data are available in suitable formats for analysis, but the original projectile point analysis was too general for the purposes of this study (see Rice 1994 for details). Points were divided into longer or shorter categories and subdivided by several attributes (e.g., blade, base, or notch shape). Geometric morphometrics (GM) is a set of methods designed to quantitatively analyze shapes and is ideal for projectile point analysis. See Bischoff (2023) for details on GM and the methods used to analyze these projectile points. A GM analysis was conducted on the 2D outlines of each complete triangular or side-notched projectile point. The majority of projectile points were triangular or side-notched. The few other points were likely curated points from earlier periods. Figure 4.2 and Figure 4.3 show the results of these analyses. These figures demonstrate how GM methods can calculate the similarity between each projectile point shape. These results were classified into closely related clusters and used in the same way as ceramic types.

4.5 Results

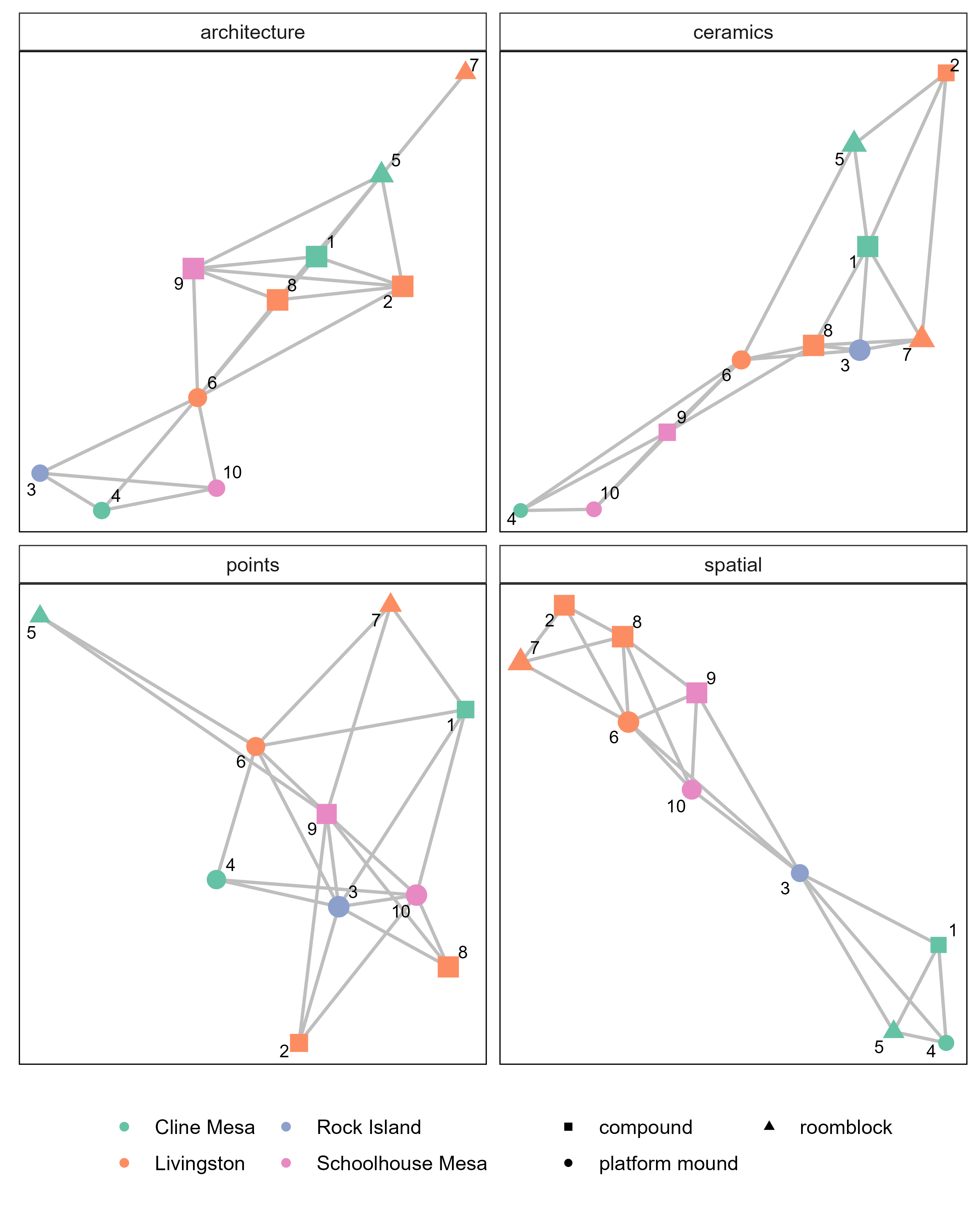

Figure 4.4 shows the networks with the top three strongest ties between each node. Immediately apparent is that the area groupings identifiable in the spatial network are intermixed in the other three networks. Likewise, the main architecture features that are clustered in the architectural network are also intermixed in the other networks. This indicates there is no strong spatial or architectural visual patterning in the networks. Although, there are some elements that appear influenced by space and/or architecture.

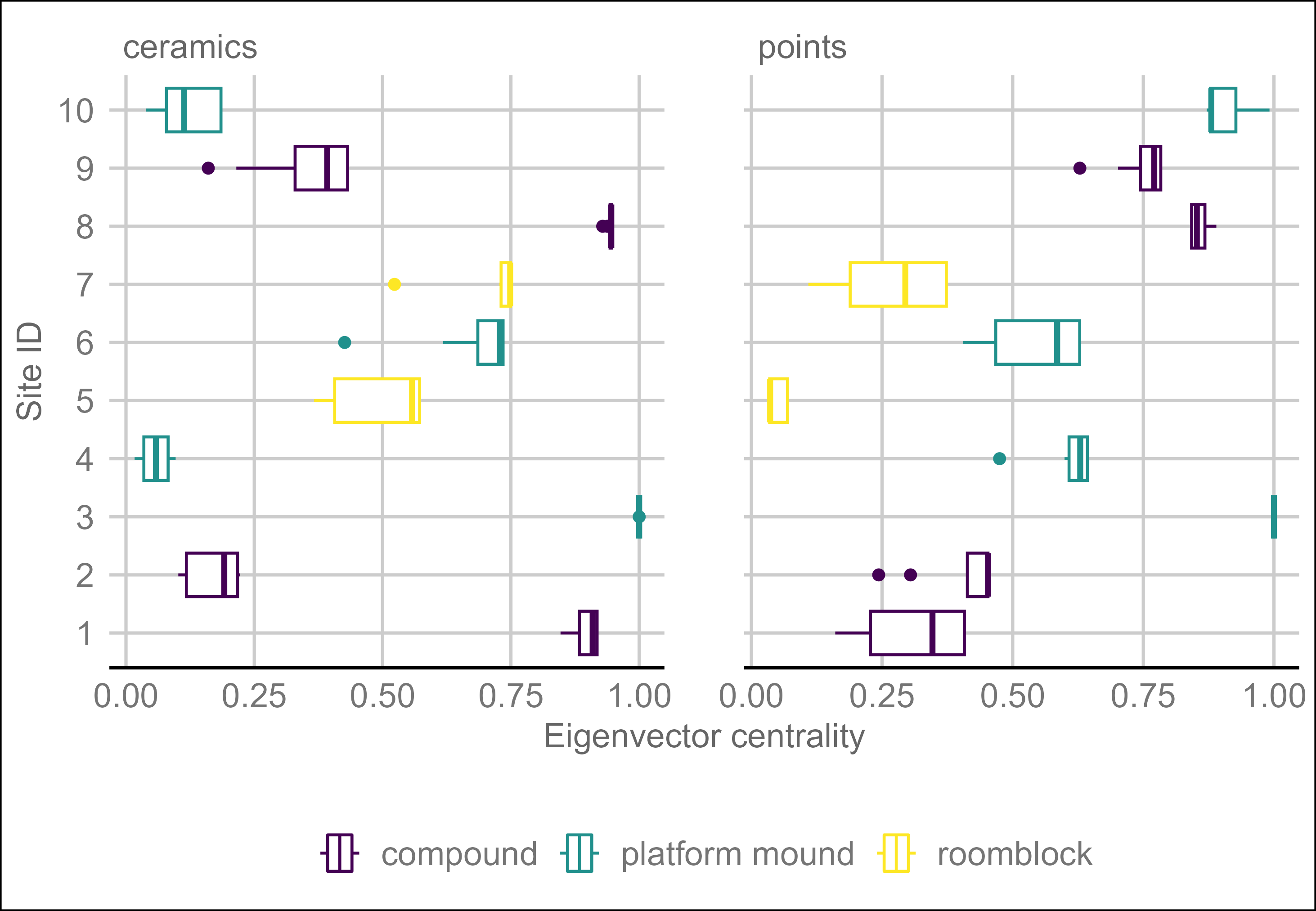

Bass Point Mound forms a crucial bridge between the Cline Mesa sites and the rest of the network. Because the network is not complete, one cannot argue that there were no other sites between Cline Mesa and the Schoolhouse Mesa sites, but it still represents an intermediary location. Its geographic position overlooking the confluence of the Salt River and Tonto Creek would make an ideal meeting place for parties coming down from the Tonto Creek arm of what is now Roosevelt Lake or coming up from the Salt River arm. The Rock Island area consists of a single site in this study, Bass Point Mound (a platform mound), although it was not heavily excavated. If spatial distance was an important factor in social interaction, then we would expect Bass Point Mound to consistently be a highly central node due to its central location. This is exactly what we see in the ceramic and point networks in Figure 4.5 with Bass Point Mound always the most central node.

Figure 4.5 also demonstrates several contradictions between networks and between sites with the same main type of architecture. Only the roomblocks consistently group together, as the compounds and platform mounds are inconsistent in both networks. Only three of the sites (Bass Point Mound, Pinto Point Mound, and the Sand Dune Site) have consistent centrality across both networks. The roomblocks have above average centrality in the ceramic network but the lowest centrality in the point network. Table 4.2 shows the eigenvector centrality vectors for the ceramic and point networks by type of architecture with the mean for both networks. Surprisingly, the platform mounds are the least central, on average, for the ceramic network, but they are the most central for the point network. The roomblocks, on the hand, are the most central for the ceramic network and by far the least central in the point network. Clearly, there are major differences between these two networks.

| architecture | ceramics | points | mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| compound | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| platform mound | 0.37 | 0.72 | 0.54 |

| roomblock | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.27 |

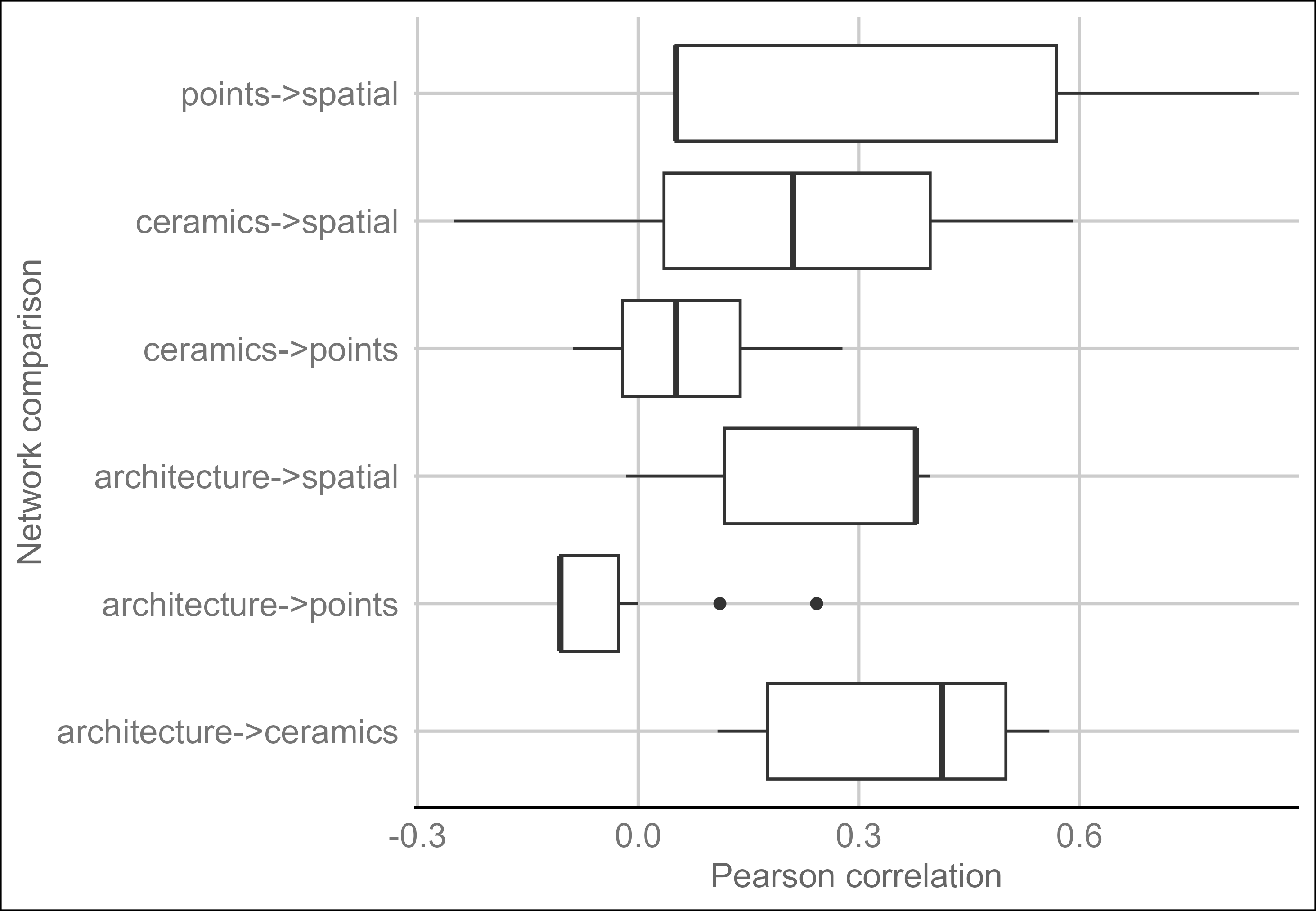

The multilayer Pearson correlation provides a more direct way to compare these layers, as shown in Figure 4.6. This analysis provides a clear contrast between layers. Only the architectural and point networks show a negative correlation–meaning that ties existed in one network where ties did not exist in the other network. And only one comparison has a relatively strong correlation–the architecture and ceramic networks were strongly correlated (\(r\) = 0.546). The visual inspection and centrality analysis provided some indication of this, but the multilayer network comparison provides further evidence. The other networks all show moderate correlations with space, which is probably driven primarily by Bass Point Mound.

4.6 Discussion

This analysis has three main findings regarding networks in Tonto Basin: (1) that architecture and ceramic networks are correlated; (2) that roomblock sites are moderately central in the ceramic network but have low centrality in the point network; and (3) that ceramic and point networks have significant differences. In terms of the null hypotheses stated in the introduction, there was some spatial correlation, but it appears to have been driven primarily by one site. Given these network results, how might they be interpreted in terms of social behavior?

Exchange would be a primary driver in these network dynamics, and clear evidence exists for exchange of several types of material culture. Trade within the basin does not appear to have been dominated by any one group and may have been competitive in nature (Rice et al. 1998, pp. 127–128). Ceramic exchange certainly occurred at a regional level, but even local ceramics were circulated within the basin (Heidke and Miksa 2000; Miksa and Heidke 1995; Stark and Heidke 1992), possibly in return for food (Jeffrey J. Clark and Vint 2004, pp. 290–291). Projectile points (either as part of the arrow or separately) may have also been commonly exchanged. There are several examples of the exchange of bows and arrows ethnographically throughout the world (e.g., Mauss 1966; Nishiaki 2013; Wiessner 1983), in North America generally (e.g., W. J. Hoffman 1896; Radin 1923), and in the Southwest specifically (e.g., Beaglehole 1936; Dittert 1959; Fewkes 1898; Griffen 1969; Parsons 1939; Simpson 1953). Besides Watt’s study of knappers, Sliva’s (2002, p. 539) analysis of sites from another Roosevelt project suggests craft specialization in projectile point production. Mortuary offerings were possibly the intended function for many points (Sliva 2002, p. 543), which may have spurred the increased craft specialization. Shell and stone jewelry, among other artifacts were also produced and exchanged within the basin. Potential loci for exchange are the platform mound sites. The purpose of these sites is debated, but many argue that they served an integrative function (e.g., Abbott et al. 2006; Adler and Wilshusen 1990; Jeffrey J. Clark and Vint 2004; Craig 1995; Craig and Clark 1994, pp. 112–165; Doelle et al. 1995, p. 439). If platform mounds were places where exchange between communities regularly took place, then we would expect platform mounds to have higher centrality. Centrality varied among the platform mounds, but on average, platform mounds did have the highest centrality–if narrowly.

As discussed previously, cultural differences were expected between the Tonto Creek and Salt River arms of Roosevelt Lake. This was due in part to differences in long-distance ceramic exchange and obsidian sourcing (Lyons 2013; Simon and Gosser 2001). This analysis did not use obsidian or focus on non-local ceramics and therefore did not capture differences based on these factors. There was some expectation that more separation in the material networks would be apparent between the Cline Mesa sites in the Tonto Creek arm and the other sites (minus Bass Point Mound that lies at the confluence). This was not born out in the visual inspection of the analysis with significant mixing of the areas in the network.

There is a potential chain of association between immigrants and roomblocks, roomblocks or locations with roomblocks as centers of Salado production, and Salado pottery as a widespread phenomenon that provides an expectation for roomblock sites to be central to pottery networks. While this association is circumstantial and not expected to be uniform across the Hohokam region, roomblocks did have the highest centrality in the ceramic networks. Another proposed reason for the high centrality of roomblock sites is that they lacked access to adequate farmland and had to trade pottery for food (Jeffrey J. Clark and Vint 2004, p. 291). This second explanation may help explain why roomblock sites had low centrality in the point networks, presuming that points were not exchanged for food. It is beyond this simple analysis to determine the precise reasons, but clearly roomblock sites were important for ceramic circulation. On the other hand, sites with roomblocks had the lowest centrality in the point networks. This suggests that the influence the occupants of roomblock sites had in pottery networks may not have extended to other spheres of interaction.

As discussed previously, my simplistic model of interaction in Tonto Basin assumes that the ceramic network represents categorical identification among women. Recall also that I expected architecture to represent categorical identity. Thus, the correlation between architecture and ceramics is an expected find and good corroborating evidence that these types of material culture represent markers of identity demonstrating belonging to a particular social group.

The point networks were expected to represent relational identification among men, at least in this case study. Because relational identification is related to frequent interaction, spatial distance is a crucial component. It is much harder to interact with someone when they are far away. Thus, the correlation between the point and spatial networks, though weak, also makes theoretical sense.

Perhaps the reason roomblocks were more central to the ceramic network is because immigrants to the basin had less access to farmland and had to make pottery to get food, as mentioned. This would explain higher centrality for roomblocks and lower centrality for point networks. It does not explain the remaining differences between point and ceramic networks. Projectile points at least were highly gendered, and ceramics probably were as well. The evidence presented here demonstrates that ceramic and point networks vary significantly, and gender likely played an important role. More research will be needed to determine the relationship between gender roles and material culture networks and to determine the relationship that immigration played in these dynamics.

4.7 Conclusion

This is one of the first archaeological applications of multilayer network analysis to consider multiple types of material culture. This is advantageous for studying how types of material culture do or do not co-vary, which aids interpretations of the social interactions that created these patterns. This analysis used architectural, ceramic, projectile point, and spatial data from 10 sites in Tonto Basin focusing on occupations from the Roosevelt phase dating between AD 1275 and 1325. A network was created for each type of data and combined into a multilayer network. Visual network analysis, eigenvector centrality, and multilayer network Pearson correlation were used to study and compare the networks. The findings indicate that the ceramic network was strongly correlated with the architectural network. Furthermore, sites with roomblocks indicative of immigrants from the north and east of Tonto Basin were, on average, the most highly central sites in the ceramic network; however, they were the least central in the point network. Immigrants may have relied on pottery production to integrate with the local networks, but this relationship did not hold for projectile points. Finally, the results demonstrate notable differences between the ceramic and point networks. This finding has major implications for network studies because many rely on only a single artifact type. If different types of material culture do not co-vary regularly, then that indicates archaeologists must do more to include other types of material culture to better understand the complex social networks that existed in the past. Furthermore, projectile points and ceramics have strong associations with gender. Differences in the ceramic and point networks suggest differences existed between the social networks of men and women.

This analysis used a handful of sites from Tonto Basin. Much more data exists and the results discussed here would be greatly strengthened by including more sites and data. What would be perhaps more useful would be to include sourced obsidian and ceramics. Networks created from artifacts where the origin is known can be used to more strongly infer various types of social interaction. The role immigration played in the social dynamics of Tonto Basin as represented in material culture networks also deserves consideration. This type of multilayer analysis would also be useful to conduct in other regions. It would be particularly useful for comparative studies to know in what circumstances different types of material culture do or do not co-vary. It is my hope that this study highlights the usefulness of a multilayer network approach utilizing multiple types of material culture.

Data Availability

All data and scripts used in this analysis, except site location information, are available at the following DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/T8QWF and Appendix C.

Note: This paper has been published in the journal Kiva and is available at DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2023.2235137.

Permission to publish in the dissertation was retained when the article was submitted–see Taylor and Francis permissions in Appendix E.